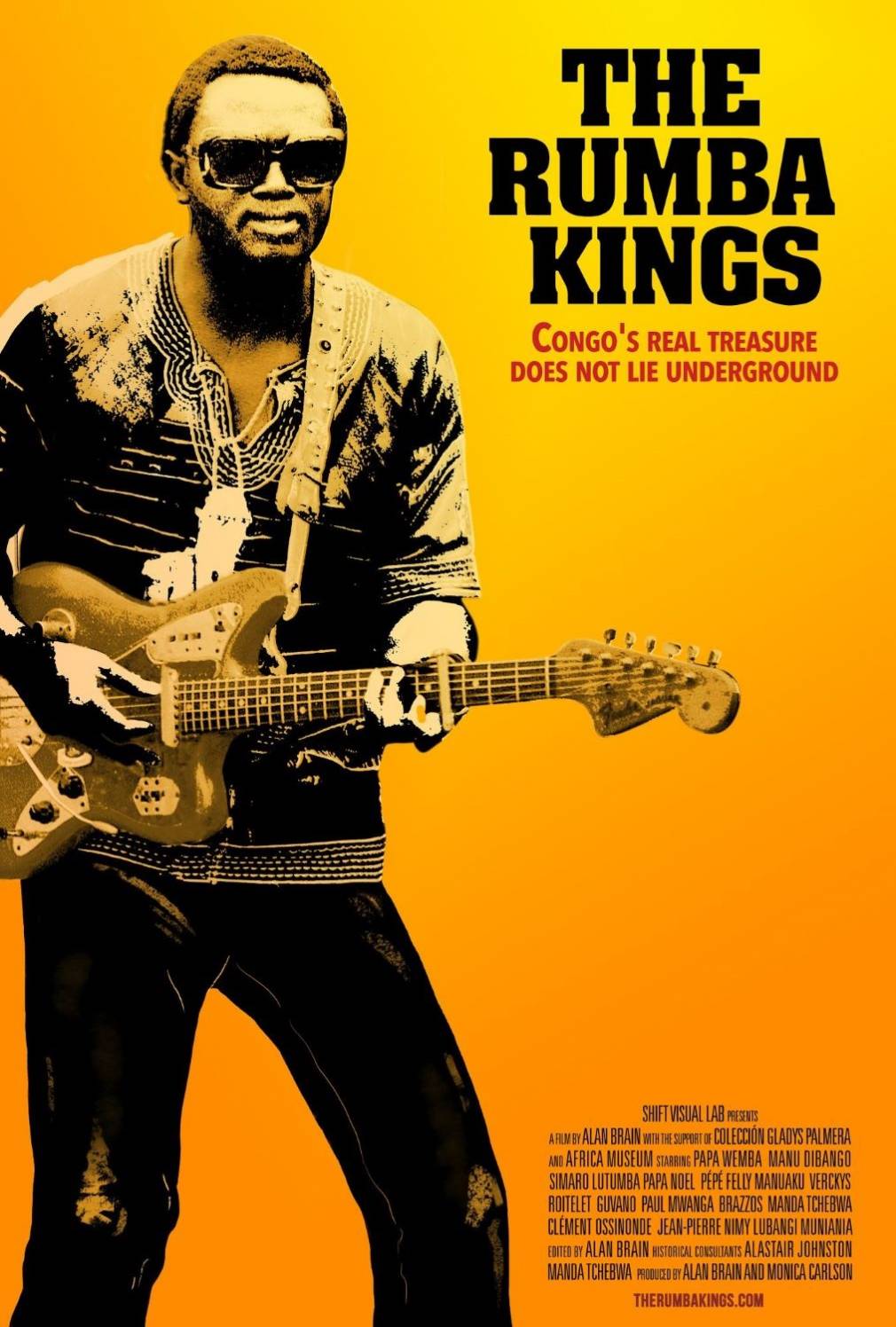

Two years after PAM told you about The Rumba Kings – dedicated to the golden age of Congolese rumba – the film is finally being released. The DOXA festival in Vancouver – held online this year – has selected the film and will screen it on 6th May.

The Rumba Kings, a documentary film by Alan Brain that traces the history of Congolese rumba and its contribution to world music, is finally being released. North American audiences will be the first to see it when it is broadcast online at the DOXA festival in Vancouver. This will take place on 6th May – don’t miss it! Without doubt the hour-and-a-half-long film is the one that all you music lovers have been waiting for.

Why is that? Well first, because it pays tribute and does justice to this original sound, born of the meeting between Congolese and Cuban rhythms after the slave trade had scattered the children of Africa all over the lands of America. Their sounds (cha-cha, montuno, bolero etc.) then returned to Africa, like a letter addressed to a mother back home. The film, by Peruvian director Alan Brain, who worked for the UN in Kinshasa for several years, traces the course of this history and takes us back to the crucial years preceding the Congo’s accession to independence. It was in two crucial decades, between the 1940s and 1960s, that Leopoldville (now Kinshasa), as well as Brazzaville, gave birth to the music that would make the whole of Africa dance. The roots of rumba are illuminated with the help of archives that show the markets, the ngandas, and the dandies photographed by De Para, as well as the crowds at the crossroads listening to the radio.

Second, this film shows that rumba is the bearer of life, enthusiasm and hope, the soundtrack of resistance to colonisation, where, in the Belgian Congo perhaps more than anywhere else, the people had found themselves enslaved once more. Better than simply the soundtrack of resistance, Congolese rumba is resistance itself. This message is one of the film’s main aims and it dexterously tells the story in both a scholarly and chatty way, by having the survivors of the golden age of the genre testify, taking a valuable step back to the 1950s. We see an emotional Brazzos and Roitelet, who were at the beginnings of the OK Jazz Orchestra, as well as percussionist Petit Pierre – the only survivor of the African Jazz adventure in Brussels, where the “Independence cha-cha” was born (Brazzos has since died). Along with them are featured Simaro Lutumba the poet and Franco’s right-hand man, Guvano the pillar of the African Fiesta National, Papa Wemba, Manu Dibango… half of these incredible witnesses have now left us but all of them appear in this ensemble film and lend it the weight of their experience and their sincerity.

The film is generous in its sincerity and emotion. Some veterans like Kuka Mathieu (one of the former members of African Jazz and the Vox Africa Orchestra) can still be found in Kinshasa, singing old tunes with all his heart and a miraculously intact voice. It is clear that director Alan Brain has fallen in love with rumba and the Congo (but can you love one without the other, and vice versa?) It took patience to find all these scattered and lost archives and bring them back to life. In The Rumba Kings, you will see previously unseen archives of Nico Kasanda alias ‘Dr. Nico’ launching into a wild solo, as well as Franco and his incredible art of improvisation (both musical and verbal). We also get a glimpse of the classic age of rumba with Le Grand Kallé, who was its first chief. Rochereau’s fans will be left wanting more, but the release of such a film should put an end to any quibbling so that the greatness of the rumba can, quite simply, shine. And that is precisely what this film manages to do. PAM says long live The Rumba Kings!

If you live in Canada (or have access to a Canadian IP address) you can buy a ticket to watch it (virtually) here. If not, keep up to date with the film here.